The journey to here

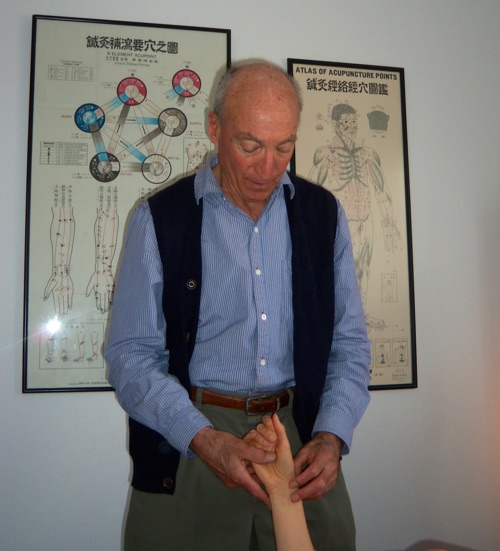

Stuart Bernstein began practicing acupuncture over forty years ago, when acupuncture in the U.S. was in its formative stages. The following interview reveals his journey from being trained as one of the first American-born practitioners of acupuncture to the development of his present work.

Interview

Q: Why did you choose to become an acupuncturist?

A: I’ve always been troubled by the suffering in this world, but I never felt called to become an M.D.

During the 70s, I was working as a freelance writer and a wilderness guide. When my wife and I moved to a northern New Mexico village with our infant son, the locals encouraged me to join the volunteer ambulance corps. I trained as an Emergency Medical Technician.

In the ambulance rides from mountain villages to the hospital I was passionate about helping stabilize a person. But once we arrived at the hospital, my job was done. We dropped the patient off, turned around, and most often never saw that person again. That was hard for me.

Q: So then you decided to learn acupuncture?

A: Not exactly. I worked off and on as an EMT for several more years, but emergency medicine didn’t feel right to me. It gave the appearance that we were a society of accidents, tragedies, and disasters just waiting to happen. I didn’t feel aligned with that crisis reaction model.

Freelance writing had become more and more my passion. But one day I hit a wall. I couldn’t break through.

I heard a voice within say that before I could write what I had come to write, there was something I must first master. I had no clue what that something was.

Q: Did you find out?

A: Yes, but it took years. It started with my wife getting sick. When modern medicine couldn’t touch her condition, a neighbor recommended some “wizard healer, a Sensei in Santa Fe.”

We drove to his acupuncture office twice a week. While she was being treated, I took care of our baby and read back issues of National Geographic whenever he slept.

After I’d read all the magazines, I found a small book at the bottom of the pile. It described an ancient principle, long hidden, as the foundation for the author’s healing work. The author was the acupuncturist in the next room.

His words felt so fresh, not based on a religion or an ideology. The words moved me.

Q: So that’s when you knew you wanted to study acupuncture?

A: Not even then yet. The Sensei offered an intensive in aikido and natural life therapy. I went. It was there that I saw he really had the big picture, knew how healing worked and, most important, what a human being was.

Then, when he announced months later that he was opening a school, I knew I had to attend.

Q: So your future had come clear.

A: Well, I certainly didn’t see how things would unfold, but I had taken the first step. In the school, I found every class riveting. I realized I was finally learning how to live. I was studying with a world-renowned teacher, a man who was a pioneer in acupuncture and natural healing. He was illuminating the components for being human. I could not have asked for more.

Q: So when you finished school, you opened a practice?

A: Yes. The Sensei saw his students creating acupuncture practices as a way to work with the principle behind acupuncture, as did I, at least at first.

Q: You stopped?

A: In a way. Even before I turned professional, I found I had a capacity for acupuncture. I was having a good deal of success in treating people as a student, and I found myself liking that more and more.

Q: Nice.

A: Call it what you will. But my focus was shifting from the principle behind acupuncture to acupuncture itself. I was inviting in danger.

Q: What do you mean, danger?

A: My practice grew. Some patients came from great distances for treatments. I had a long waiting list. But really, I’d walked away from my true purpose and taken the glamour bait. I’d turned greedy to heal others. Greed always presents danger.

Q: Did you see it?

A: I chose not to. I was attached to the accolades. One day a poet patient of mine asked me to have tea with him, said it was urgent. He told me his wife had left him and he felt broken. “It happens to those of us who least expect it,” he said, looking beyond my eyes.

A year later to the day, it happened to me. The divorce was the correction for my swelled head. My world went dark. I essentially lost my children from that marriage.

Q: Sounds severe.

A: Ultimately, it wasn’t. It was what I needed. The wound remains, even now, but it spurred me on.

Q: How so?

A: Amid the ruins, I was called to go deeper. Slowly, I got back on course with what I needed to learn, what I needed to “master.” I could no longer focus on simply fixing diseases. I felt called to seek out the origin of illness and well-being.

The suffering of human beings, my own suffering, compelled me.

Over time, I saw how we torture ourselves and make ourselves ill, how we make ourselves well, how we make choices as individuals that affect the collective and how the collective affects us as individuals.

Q: Sounds like your life took a radical turn.

A: It did. Once I realized it was not good for me to look out for confirmation or approval, my attention turned inward for the answers to my search.

What had initially called me to study with the wizard was the unique principle veiled at the core of acupuncture, something most practitioners are not conscious of. He removed the veils, handing my classmates and me a principle that provides people the tools for realizing their full capacity as human beings.

When I returned my attention to helping develop these tools, I slowly gravitated to my confidence.

Q: That must mean you’re writing again.

A: I am. The time came when I felt clear that I was grasping the essence of illness and of well-being. My writing now focuses on what is possible if only we make the changes we are capable of making.

Q: Is there anything you’d like to add?

A: Yes. My teacher, O Sensei M.M. Nakazono, explained that the pyramid of health care is upside down. We have made modern medicine the foundation for our health care. Acupuncture resides somewhere near the top of this pyramid.

If we persist in upholding our current model of health, it will bankrupt us, regardless if people have national health care, private insurance, or no insurance at all.

Q: Certainly you’re not saying modern medicine isn’t valuable?

A: No, it has its place, especially in the world we’ve created. The problem is that our dependence on modern medicine does not place the responsibility for well-being where it belongs. We will only grow poorer and sicker as long as we lean on this model.

Here’s a different perspective for you:

A long time ago, before acupuncture ever existed, if a man strayed from his capacity for caring for himself and from his life’s purpose, it took only a word or two from a member of his community to get him back on course.

But once we began developing this material-scientific civilization, maintaining our inner balance became increasingly difficult. People started to require counseling in proper diet. At some point, they needed something more, so acupressure was introduced.

Over time, acupressure was not enough. That’s when the use of moxabustion, a form of heat therapy on specific acupoints, began. Eventually, acupuncture, which is a form of surgery, was required for maintaining people’s health.

Finally, acupuncture was not enough—more invasive forms of medicine were required. Allopathic, or modern, medicine was eventually invented at the time of the industrial revolution. Modern medicine serves to get a worker back on the job quickly, but at what cost?

Today, we are transitioning out of an industrialized worker’s world. This could be an optimal time for us to turn around our health care system, and ultimately return to a world where we could get back on course with only a few words from someone. I consider this to be societal healing, beginning with family or someone in your family..

Q: Sounds ambitious.

A: Perhaps. But we can’t cure our present predicament by persisting with the viewpoint that created the mess in the first place.

I could say more, but since our world leans too heavily on information, a collective disposition of ours, I recommend that you feel my words to see what they stir up for yourself.

Q: Ahh. Thank you.

A: Thank you.